The early success of the Democratic “resistance” efforts in opposition to Trump Administration policies has emboldened Democratic activists and has many calling for a “Liberal Tea Party.” They see obvious parallels between their own massive rallies and town hall protests and the enthusiasm that developed on the right in 2009 and 2010 in response to the stimulus and health care bills. Understanding the electoral gains that Republicans achieved in subsequent years, liberals want to mimic Tea Party tactics – ideological stridency, with primaries for members of their own party who go “soft” – in order to push their agenda and oppose the Trump Administration.

This is an almost impossibly terrible idea.

First of all, it’s based on a myth. Tea Partiers, along with a frequently lazy media more interested in narratives than analysis, have mistaken correlation for causation and credited the Tea Party for recent Republican electoral successes. It is of course true that the 2010 midterm elections were a landslide for the GOP. Republicans gained 63 seats in the House and six in the Senate in the wake of the Tea Party uprising. But what happened in 2010 was much more of a return to the status quo than a sudden uprising created by a new Tea Party-infused brand of conservatism.

As I charted in my previous post, the Democratic majorities built in the 2006 and 2008 elections are outliers over a 20+ year period. In 2010, the map largely reset, and districts and states that had been trending red for more than a decade fell back into the GOP fold. That’s regression to the mean, not a revolution.

In fact, there is ample evidence that Tea Party candidates hurt the electoral prospects of Republicans in key competitive races. The nominations of Sharron Angle in Nevada and Christine O’Donnell in Delaware almost certainly cost the GOP two seats in 2010, and Richard Murdock in Indiana and Todd Akin in Missouri cost the party two more in 2012. Without those seats (and others where the party nomination process pushed too far to the right), all of which were strong opportunities for pickups bungled by extreme and unqualified candidates, Republicans had to wait until 2014 to take back the Senate majority.

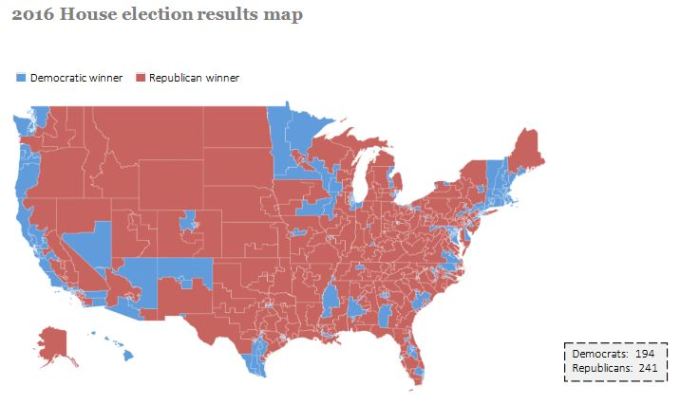

What Tea Party-backed candidates have been successful in doing is turning solidly red districts even more red. While having more extreme members from already partisan districts may be psychologically empowering for those with a strong ideological bent, it is a particularly useless endeavor for Democrats at this point. The party is operating a structural disadvantage due to the poor geographic alignment of their constituents (who are almost exclusively grouped in coastal and urban areas) and the aggressive gerrymandering undertaken by Republicans since the 2010 census. There simply aren’t enough blue or near-blue districts to be won with more staunchly-partisan Democrats.

As the centrist Democratic organization Third Way recently pointed out, “you can walk from the Atlantic to the Pacific and not step in a blue county.” In order to regain majorities and attempt to actually govern under their principles, Democrats will need to find ways to increase their strength in areas that are currently red. That will almost certainly require more moderate members of the party, not fewer.

The impulse toward Tea Party-style primary challenges of Democrats who do not sufficiently “resist” Trump is particularly suicidal in the 2018 Senate elections. There are ten Democratic Senators up for reelection in states won by Trump: Bill Nelson (D-FL), Joe Donnelly (D-IN), Debbie Stabenow (D-MI), Claire McCaskill (D-MO), Jon Tester (D-MT), Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND), Sherrod Brown (D-OH), Bob Casey (D-PA), Joe Manchin (D-WV), and Tammy Baldwin (D-WI). Trump won half of those states — Indiana, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota and West Virginia — by double digits. By contrast, there is just one Republican (Dean Heller of Nevada) who’ll be seeking reelection in a state won by Hillary Clinton. Forcing these members to the left, or replacing them on the ballot with more liberal candidates who lack the benefits of incumbency, is much more likely to grow the Republican majority than it is to upend and replace it.

There is perhaps no better example than Senator Manchin. Liberals loathe him for breaking with party orthodoxy on a variety of key issues, including environmental regulations, gun control, and certain LGBT rights legislation. He’s also gone out of his way to cozy up to Trump, publicly visiting Trump Tower during the transition and voting in favor of several of the President’s Cabinet appointments.

But there is a strong case to be made that Manchin is, in fact, the most valuable member of Congress, for either party. Even if the only vote Manchin cast with his fellow Democrats was for Chuck Schumer as Majority Leader (and he actually votes with the party about three-quarters of the time), this would still be true. In November, Trump won West Virginia 69% to 27% over Hillary Clinton. In 2014, Senator Shelley Moore Capito beat her Democratic opponent by about 30 points.

No one else outperforms his or her state’s partisan demographics the way Manchin does. No, he’ll never vote like Elizabeth Warren does, but Warren represents a state that will elect almost any warm body with a D next to its name (except this one). Going after him in a primary is tantamount to throwing away a seat the party has no other avenue to win.

Of course, Tea Partiers and those looking to mirror their tactics on the left would argue that winning elections is only part of the battle. It is also critical, they would contend, to hold members’ feet to the fire and push their issues legislatively. But the Tea Party example has largely failed in this arena as well.

By maintaining absolutist positions and refusing to accept measures that moved only incrementally toward their goals, the Tea Party (and their descendants, now known as the Freedom Caucus) have prevented Republican majorities from passing key measures to, for example, fund the government and avoid a devastating national default. Operating as a bloc that rejects anything less than 100% of their goals, they have repeatedly forced Republican leadership to go to Democrats in order to secure votes. This self-defeating effort has naturally pushed legislation to the left, against the Tea Party’s stated agenda and interests.

Democrats should avoid the simplistic temptation to try and copycat Tea Party methods, and instead focus on the less sexy but much more effective strategies of growing their tent and welcoming a wider array of members in their caucus. Electoral and legislative realities simply do not allow for any sort of immediate, uniform surge to the left. If the party wants to succeed, it must understand that accepting that the most electable liberal candidate is preferable to the most liberal candidate, and realize that this means some goals will come only incrementally.

Building a party is about finding converts, not heretics. Tea Party-style attacks on the moderates will only further relegate the party to obsolescence at all levels, and ensure that none of that agenda ever gets a chance to be enacted.

Nice piece!

Sent from my iPhone Les Bowman

>

LikeLike